Economics Is a Bullshit Science

Nothing better illustrates the utter mindboggling craziness of neoclassical economics, than its Nobel laureate in environmental economics.

One of the most salient features of our culture is that there is so much bullshit. Everyone knows this.

This is a long piece about an important topic, so strap in and let me take you for a ride. No maths, (sidenote: No mathematical equations, that is. I do talk about the topic of mathematics as a matter of life and death. )

The Wall Street crash of 1987 changed my life

As a young guy, I was involved with a group that was trying to get our own housing coop built. But we couldn’t. The interest rate was too high. Our calculations were based on paying rent for 50 years. That gave us a 50-year budget to pay off the loan for initial investment of building our flats, and for ongoing building maintenance. And then a sizeable budget for paying interest over our loan. But not an unlimited budget. We were poor. And the interest rate at that time was above 6%. The cost was prohibitive, blocking us from realizing our dream.

Mid-September, we were out of options. I remember sitting on the beach after having given a press conference in the capital, which nobody attended. My head buzzing with despair. I was a young father, dirt poor. This was my one shot at providing a decent place for my baby girl to grow up. It was not working out. What now?

A New Hope

Then Wall Street crashed. The interest rate dropped below our maximum boundary of 5.6%. A better future started unfolding for me.

Suddenly, we had a viable business model for our housing coop. We secured funding, with which we could pay our architects and have our own housing block built. Two years later, we moved in. Our intentional community became a reality. My daughters grew up in the safe and nourishing environment of the communal garden, next to their Waldorf school, in a vibrant city. We were all embedded in a rich network of social connections. I lived a significant chunk of my life there, with my children and both of my ex-wives. Don’t ask.

The poisoned well: studying the dark arts

One year after moving in, I enrolled into university. A conscious decision to study the dark arts, the black magic of economics. I was determined, to try and understand how my life could be decisively routed onto a different track, by something as abstract and distant as the New York stock exchange.

I went over to the dark side. But not really. I kept my distance from the loud frat boys, and the high-potentials that got headhunted by Shell. I learnt a lot and am still unlearning a lot of that.

Here’s one thing I learnt though: prominent economists sometimes just Make Shit Up™ in the service of political goals. My master’s thesis was on environmental economics. I dissected the arguments used to justify a major infrastructure investment. When it was decision cruch time, a well-timed report by a prominent and politically well-connected economist sealed the argument.

Toddler maths in a fancy suit

Here’s the crux: the math in the report had nothing to do with the infrastructure project it was applied to. And that math was dead simple: a linear correlation. The report just assumed that investing in infrastructure always pays off, and pays off more if you invest more.

That’s toddler level — more cookies — maths, wearing a fancy suit and pretending to know stuff you cannot possibly understand. Assumptions presented as outcomes. Remember this theme: it’ll return below, in the context of life and death for the whole planet. Toddler maths in a fancy suit.

Somebody at the time joked, that you could have used that report to justify covering one of our islands in asphalt: the report’s logic would confidently justify that investment.

I graduated with distinction and went off to do something completely different with my life. Another story.

Outdated physics for a brave new world

Economics is full of interesting concepts and mathematical tooling. Much of it neatly extended my high school training in classical physics. If you understand the first- and second-order derivatives involved in the parabolic curve of an object falling in gravity, you’re good to go. Quadratic curves are the economist’s hammer, and the whole world is their nail to hit.

The same maths are used all over the place in economics. That’s not a coincidence.

Neoclassical economic theory was created by substituting economic constructs derived from classical economics for physical variables in the equations of a soon-to-be outmoded mid-nineteenth century theory in physics. […] In the mathematical formalism that resulted from these substitutions, the economic actor is presumed to operate within a field of force identified, in both figurative and literal terms, with energy.

(L. Hunter Lovins, cited in Bardi and Pereira 2022)

That body of theory is only workable if you swallow its foundational assumptions hook, line and sinker. Nineteenth-century physics sees the world as a dead, inert space, in which atoms collide like billiard balls. If you import that world-view into a social science like economics, you’re thinking of people as atoms. Separate, isolated people, buffeted by force fields beyond their ken.

No wonder they call economics the dismal science. It’s an incredibly reductive approach to social dynamics. And it’s outdated. Physics itself has moved on. A century ago, Einstein and quantum mechanics showed, that our cosmos is not an inert space with bouncing objects. It’s far more magical.

The revolution in physics (relativity and quantum mechanics) shattered virtually every major postulate of the Newtonian worldview. […] So counterintuitive were its findings that wile scientists largely agree on the mathematics of quantum mechanics, there has been no consensus on its implications for our understanding of the nature of reality. Sixty years after the quantum revolution, most academic disciplines have not fully appropriated its significance and continue to conduct their business as if the world of the rationalist enlightenment were still intact.

I’ll have much more to say about this paradigm shift in future blog posts. In a sense, it’s what this whole blog is about. For now, back to economics. It sees people as separate, competing for scarce resources. But is that how the world really works?

Biologists now know that nature is based more on cooperation than competition. The best of modern science tells us that the neoliberal narrative is just bad science.

(L. Hunter Lovins, cited in Bardi and Pereira 2022)

If only you knew the power of the Dark Side

Figure 1: Darth Vader: If only you knew the power of the Dark Side

If economics was just a load of bad ideas, well too bad but who cares? Astrology is a worse pile of crap, and you can just safely ignore that. Except, you can’t ignore economics. More precisely: you can try to ignore economics, but it won’t ignore you.

Economic thinking has infested politics and the way our society is run to a deep extent. So deep, that in a way it’s become a self-fulfilling prophecy. Arrange whole societies around Thatcherite ideas of competition and a hands-off anything-goes-if-it-makes-money mentality, and what do you get? A dystopian dynamic of greed, soaring inequality and poverty.

It gets even worse, when it comes to our planetary poly-crisis. With survival of not only our species, but much of the non-human web of life hanging in the balance, bad ideas via bad policies are lethal on a massive, planetary, existential scale.

Neoclassical economics provides the ideological underpinnings, of the global death cult called capitalism.

The empire strikes back

Figure 2: The emperor adresses the senate

Let me introduce me to William Nordhaus. An eminent economist. He wrote the book, literally: back when I was at uni, his was the textbook we were taught. Rewind a few decades more, and he was there when the Club of Rome published their report The Limits to Growth. (Meadows et al. 1972) See my earlier blog post in this series for a summary of the report.

Nordhaus penned a vicious attack on Limits (Nordhaus 1973), which contributed to its getting sidelined. In some kind of shady academic politics, the rebuttal to that criticism got sidelined too. (Forrester, Low, and Mass 1974) Nordhaus later returned for another kick in the side, to make sure the patient was not getting up. (Nordhaus, Stavins, and Weitzman 1992)

Fast-forward some more decades, and Nordhaus dominates the environmental economics scene, reinforcing the intellectual monoculture.

As any published academic knows, once you are published in an area, journal editors will nominate you as a referee for that area. Thus, rather than peer review providing an independent check on the veracity of research, it can allow the enforcement of a hegemony. As one of the first of the very few Neoclassical economists to work on climate change, and the first to proffer empirical estimates of the damages to the economy from climate change, this put Nordhaus in the position to both frame the debate, and to play the role of gatekeeper.

Solving equations, versus running simulations

I want to highlight a key point, that illuminates the clash of worldviews we’re dealing with here.

The Limits to Growth report was based on system dynamics, as I’ve described in my previous post. Its mathematics encapsulates a way of thinking, where everything hangs together via multiple causal pathways. As its name implies, System Dynamics describes systems that are dynamic. They’re a bit untidy, in that those dynamics either push towards expansion or to contraction; rarely are they balanced and static. The possibility of collapse is built into the math.

In contrast, the traditional approach in economics is to model systems via sets of identity equations. Those describe balances. Equilibrium. Hence they’re called equilibrium models. The math implies that everything is gradual and tends to stability.

Now the Limits to Growth report comes out, and a young Nordhaus is apparently infuriated that a bunch of nerdy computer scientists at the MIT presume to talk about world economics.

Historically, system dynamicists who have engaged in economic modeling have almost never been trained as professional economists. As such, they have had the advantage of being able to think about economic problems differently from those who have been trained along traditional lines, but have also suffered the cost of being seen as “amateurs” or “boy economists” by members of the economics profession.

Nordhaus downloads and analyzes the source code for the Limits model. And he finds the equation that determines how population growth responds to economic growth. It’s utter bollocks. He graphs it and shows how it’s totally contradicted by actual empirical data. (Nordhaus 1973) In his world, that’s how you do it: you isolate a connection between phenomena, and test that connection against real life data.

Except, he misses the point. It’s not how the Limits model works. There’s not just the one connection from economic output to population growth that Nordhaus focuses on. There’s loads of other, more indirect connections too: output increases pollution and degrades agricultural land, for example; both of which then act as a brake on population growth.

Nordhaus is simply looking at one of the several equations of the model without realizing that the output of each equation will be modified by the interaction with all the other equations and that will insure correct returns to scale. This is the essence of systems thinking: that parts interact.

If you actually run the whole model, instead of isolating a single equation, the cumulative effect of all direct and indirect relations result in a correlation between industrial output and population growth that actually does match real-world data. But to get there, you have to think in terms of whole systems, that cannot be reduced to their constituent building blocks. The whole is bigger than the sum of its parts.

A clash of two world views

What we’re witnessing here is a clash between two world views. It’s expressed as a different approach to mathematics, but don’t let that distract you. This is a paradigmatic conflict.

On the one hand, there is the ivory tower of neoliberal economics, whose foundational assumptions as a discipline are, that you do economics by applying 19th-century quadratic equations to social phenomena. All within a framework that is goal-oriented towards stability. A framework that is ill-suited for understanding market crashes caused by nonlinear complexity.

On the other hand, there’s the up-and-coming world of the computer wizzkids. Their approach is grounded in the discipline of cybernetics, originating in WW2. They think about, and model, inherently instable systems with feedback loops, out of control. Any stability is transient, vulnerable to disruption. The danger of catastrophe is built into the math. Of course there are tipping points, beyond which the whole system cascades into a different state.

The emperor has no clothes

Fast forward to 2019. This same William Nordhaus is awarded the Nobel prize in Economics for his work on….. here it comes: climate economics. Specifically, the DICE model he created, which extends the standard modeling with carbon pricing. DICE stands for “Dynamic Integrated model of Climate and the Economy”. Oh, great! The guy went over to the good side? Not so fast.

After decades of hearing escalating warnings by Earth scientists, the Paris Agreement expressed a major worldwide consensus: we need to limit global heating to below 2℃, ideally to below 1.5℃, if we want to secure a livable future for our children. From a climate science side, it’s a settled reality: we’re heating the planet to such an extent, that we risk a cascade of systems failures that threatens to collapse civilization, and possibly even much of life on Earth.

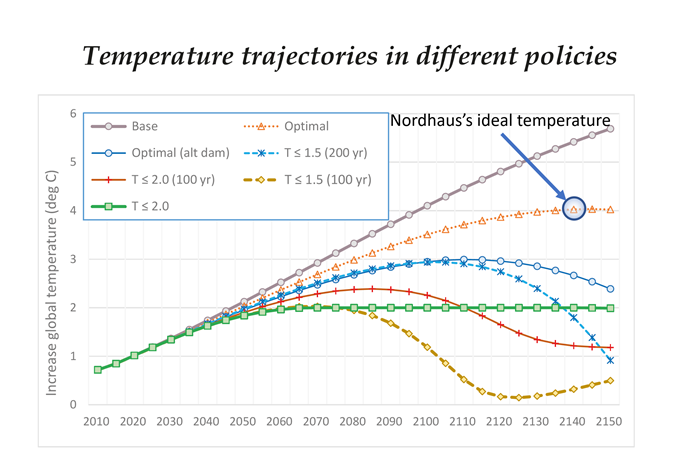

And then we have Nordhaus, one of the most prominent economists of his generation, using the platform of his Nobel acceptance speech to… argue that 4℃ global heating is “optimal” from an economics point of view. (Nordhaus 2019)

Figure 3: Nordhaus’ optimal global warming is 4℃ (Keen 2019a; annotated from Nordhaus 2019)

That’s hardcore climate denial. Advocating for 4℃ global heating, which is a level that Earth scientists agree is catastrophic, and then pretend that that’s just business as ususal, that’s climate denialism. Actually it’s worse: it’s double climate denialism. He doesn’t just deny the consequences of 4℃; he wraps it in a greenwashed sheen of having carefully taken climate change into account in his “Dynamic Integrated model of Climate and the Economy”.

All hail the quadratic equation

You’d be forgiven to think, that it’s a feat of incredible genius, to model how the whole world works, with 8 billion people and cities and infrastructures and a plethora of ecosystems interacting in myriad ways. And then to do that in a way that lets you confidently hold forth on climate change in relation to the economy. Surely that involves a stunning level of complexity that’s worthy of a Nobel prize?

Well, apparently you haven’t met the economist’s hammer yet: the quadratic equation. This is just a case of applying it to a Very Big Nail™ indeed—all of the world and our common future. At the heart of this Dynamic Integrated model of Climate and the Economy is the damage model: it calculates the (sidenote: Note that this already wipes under the rug, anything that's not expressed in money. Like, you know, the intrinsic value of the non-human world, feelings of animals, and the rumbling thoughts of ancient trees. ) damage caused by climate change.

With all the obvious complexities and uncertainties in the whole issue of how climate interacts with the economy and vice versa, Nordhaus chose to use the second-simplest relationship possible between two variables: a quadratic. He simply assumes that the relationship between change in global temperature (relative to the level in 1900) and reduction in GDP is a function of the temperature difference squared:

“The current version assumes that damages are a quadratic function of temperature change and does not include sharp thresholds or tipping points” (Nordhaus)

(Keen 2019b (quoting Nordhaus))

More heat, more damage. Add more heat again? You’ll get more more damage. Easy, right? There you go, the future of mankind and all the non-human world reduced into a single simple equation.

Remember the toddler maths in a fancy suit theme I introduced at the beginning of this piece? Well, if you try really hard it will land you a Nobel in economics. Cookies!

Garbage in, garbage out

How Nordhaus obtains those model outcomes, is a classical example of what in computer science is called: garbage in, garbage out. His fancy Nobel-winning model is worthless, since it encodes faulty assumptions and uses flawed data.

Bizarre assumptions end up in IPCC reports

To name a few of those faulty assumptions: climate change is assumed to not affect 87% of the economy, because most work is done indoors. That’s right, almost every economic activity is happily insulated from possible climate disruption. (Keen 2019b, 2021) Nevermind what’s happening outside, your office has airco.

This is a world view, in which there are no power blackouts during heat waves. A world in which there is no causal link between climate change and the emergence of a zoonotic pandemic, causing an unprecedented economic cardiac arrest. It’s a world in which there will be no water wars, nor climate migration. There are no tipping points. There are no polar ice caps melting and you won’t get caught up in wildfires or political upheaval while you commute to your office cubicle. And so on.

This is the kind of economics that then ends up in IPCC assesments of economic damage to climate change. The result is an absurd situation: the climate scientists are saying that 2℃ warming is dangerous, 3℃ is terrible. Beyond that be dragons. Ice caps melting. But in Nordhaus’ expert opinion, and that of his colleagues, there will not be much of an impact on economic activity even at 4℃ global heating. Since you’re working indoors, it doesn’t matter. Just turn up the airco.

Never mind that all of New York will be flooded. As will be Los Angeles, Amsterdam, London, Sydney, and so on. What the heck, the whole of Florida will be gone. Doesn’t hurt the economy though.

Figure 4: Map of the USA with 66m sea level rise. Credit: Conspiracy of cartographers

It’s all beyond ridiculous.

Without a liveable planet, there is no economy

The only way Nordhaus can get the result that he does is if he fails to price the risk of catastrophe and leaves out a goodly chunk of the costs of global heating. In his models, he does not account for climate damages to labour productivity, buildings, infrastructure, transportation, non-coastal real estate, insurance, communication, government services and other sectors. But the most shocking thing he leaves out of his models is the risk that global heating could set off catastrophes, whether they are physical tipping points or wars from societal responses. That is why the percentage of global damages that he estimates is so ridiculously lowballed.

The idea that climate change will just take off only a small margin of economic growth is not founded on anything empirical. It’s just a kind of quasi-religious faith in the power of capitalism to decouple itself from the planet on which it exists. That’s absurd and it’s unscientific.

In this model, the economy has effects on climate, but climate has almost no effect on the economy. This is only possible, because economics thinking is so thoroughly oblivious to the ecological reality in which we’re living. Nordhaus’ failure in this is representative, not only because of his Nobel: his model incorporates optimistic “everything will be fine” estimates from other economists. (Keen 2021)

I found that the computing adage ‘Garbage In, Garbage Out’ (GIGO) applied: it does not matter how good or how bad the actual model is, when it is fed ‘data’ like that concocted by Nordhaus and the like-minded Neoclassical economists who followed him. The numerical estimates to which they fitted their inappropriate models are, as shown here, utterly unrelated to the phenomenon of global warming. Even an appropriate model of the relationship between climate change and GDP would return garbage predictions if it were calibrated on ‘data’ like this.

Economics is functioning in insular mode, disconnected from the actual Earth system it should be thinking about.

there is a major disjuncture here with the consensus amongst Climate Scientists and Earth System scientists regarding the nature and significance of changes in climate and ecosystems

(Asefi-Najafabady, Villegas-Ortiz, and Morgan 2021)

Integral Assessment Models distort reality

Nordhaus’ DICE model belongs to a class of models called Integrated Assessment Models (IAMs). The goal of these is to help us (you, me, policy makers) think about the ways economics and climate change affect each other. They’re highly influential, and used for example in the IPCC reports to help policy makers choose between emissions scenarios. Unfortunately, they’re fundamentally, fatally flawed.

In principle IAMs explore how the ‘Human System’ (essentially economic activity) affects and interacts with the Earth System, but the assumptions used to construct IAMs are unrealistic and the relation between Human Systems and the Earth System is unrepresentative. Ultimately IAMs are a symptom, a reflection of an even more profound problem with how social planners, policymakers, and global political and economic powers are dictating the way in which natural and human resources are managed (or mismanaged).

(Asefi-Najafabady, Villegas-Ortiz, and Morgan 2021)

We’re living in an age of obvious ecological catastrophe. In this hour of need, economics ideally should provide us with a compass, a map with which we can navigate our way out of this mess and towards a sustainable society. Instead, what we get from mainstream economics is a doubling down on the tired old narrative of limitless growth.

IAMs play a key role in distracting attention from the feasibility of societies and economies built around the assumption of limitless economic growth. Historical trends of natural resource depletion show that economic growth is no longer sustainable. Yet, the mainstream narrative, even among some scientists (climate, and environmental scientists included), is failing to embrace the idea that the core force driving our current environmental problems is limitless economic growth.

(Asefi-Najafabady, Villegas-Ortiz, and Morgan 2021)

Actually there’s another Nobel prize winner in economics who sounds the alarm about integrated assessment models:

despite their dominance in the economics literature and influence in public discussion and policymaking, the methodology employed by Integrated Assessment Models (IAMs) rests on flawed foundations, which become particularly relevant in relation to the realities of the immense risks and challenges of climate change, and the radical changes in our economies that a sound and effective response require. We identify a set of critical methodological problems with the IAMs which limit their usefulness

(Stern, Stiglitz, and Taylor 2022 (emphasis added))

Who ya gonna believe, me or your own eyes?

Figure 5: Death Star over Alderaan

Meanwhile, reality is fast obsoleting Nordhaus’ model; the 2023 update to the model notwithstanding. Actual recorded damages are already six times higher than his model predicts. It would be cheaper to prevent climate change, than to deal the damage afterwards.

The economic damage of climate change is already much, much worse than DICE predicted, and the economic cost of policy to fix climate change is actually negative.

[…]

Bloomberg Intelligence has the details in a new report estimating that climate disasters cost America $955 billion in the 12-month period ending May 1 this year [2025], or about 3 percent of GDP.

[…]

however you slice it, 3 percent of GDP is wildly outside the range of the 2018 DICE model, which predicts a hit of just 0.5 percent of GDP from 1.47 degrees Celsius of warming (the global average of 2024). If we’re off by a factor of six in the world’s second-largest economy, then something is seriously amiss.

[…]

“Note that the damage function has been calibrated for damage estimates with temperature increases up to 4 °C and is not well-suited for temperature increases above that range,” [Nordhaus] writes in the instruction manual. Still, even this [2023] model only estimates a 1.6 percent hit to GDP for three degrees of warming—far too small.

(Cooper 2025 (quoting Nordhaus))

It’s not just the model logic that is flawed—though it is deeply flawed, encoding an outdated world view in its maths. But even if the logic would make sense, the data fed into the model is of appallingly bad quality. How ironic, given that Nordhaus’ original attack on the Limits report was called Measurement without Data… (Nordhaus 1973).

If the Nobel in economics is spouting such obvious and dangerous bullocks as proposing we heat the planet by 4℃, the conclusion is justified that economics is a bullshit science.

Mainstream economics is less than useless in the face of climate catastrophe; it’s a big part of the problem, not part of the solution. We need a different approach.