Fly or Slow Travel? Tough Choices.

I love to fly. But it burns the planet. With a conference in Finland coming up, I’m facing tough choices. Either I fly and am an asshole again; or I’ll spend three days and a boatload of money to get to Jyväskylä, and another three days to get back home.

Living in the fast lane

I just love to fly. Totally love it. It’s my dirty little secret. Well, now it’s not so secret anymore. Never was, actually, if you know how to find my Flickr stream.

I love traveling in general. Who doesn’t? Getting out of my rut. Seeing places, unfamiliar sights and sounds. I love to travel by car, by train, by boat. And by plane.

Getting into a plane requires full submission into humiliating rituals. Cattle herding best practices, applied to humans, an art form pioneered by the Nazis, now popularized in mass tourism. I turn navigating that obstacle course into a sport, moving through the airport as fluidly, fast and relaxed as possible.

Figure 1: In transit: SFO, USA

Getting off the train, the escalator takes me right up into the airport directly above the train platform. I double-check the departure time and terminal. Extract boarding pass and id card to queue for security. Toilet bag with fluids right at the top of my bag, so I can pull them out. Watch, phone, belt, jacket and backpack into the scanning tray. Tray takes the fast lane, no inspection needed. Don everything back on.

Weave the fastest way through the stagnating, slow-motion crowd that allows themselves to be caught in the tax-free shop maze. Grab a coffee, a bottle of water, and find a chair at the departure gate. Noise-cancelling earbuds in, play one of the pre-downloaded podcasts until boarding. Get into the plane. Store bag overhead, extract phone, Kindle, earplugs and water for the trip. I always pay extra for a window seat. Say bye to loved ones, enter airplane mode. Put some music on. Taxi.

Unadulterated magic

A big push and the runway falls away. Quickly we ascend into the stratosphere. Blue sky. White clouds. The light is otherworldly, intense. The views are incredible. You can see for dozens, hundreds of kilometers.

Figure 2: Austrian Alps

I remember the Alps stretching out into the distance. The Mediterranean shining in gold.

Figure 3: Bay of Naples, Italy

I remember seeing a big chunk of Europe below me, a meandering ribbon of glistening light that must be the Rhine.

I remember the Himalayas spanning my view from left to right as far as I could see, gaps leading up and beyond into Tibet and China, the depth of which was faintly visible against the horizon.

Figure 4: Himalayas

I remember flying closely above the wind-swept peak of Chomolungma, Mount Everest.

Time keeps on slippin’, slippin’, slippin’

Into the future

Time keeps on slippin’, slippin’, slippin’

Into the future

I wanna fly like an eagle

To the sea

Fly like an eagle

Let my spirit carry me

I want to fly like an eagle

‘Til I’m free

Oh, Lord, through the revolution

Steve Miller Band, Fly Like an Eagle

The magic of flying transports me back into a child-like wonder.

Figure 5: The wonder of flying

The wonder I felt in the summer of 1972, when as a young boy we went on holiday to Italy. We traversed across the Gotthard pass. My face pressed into the car window, I drank in the majestic mountain scenery.

Figure 6: Gotthard 1972

Fast-forward to today, and they charge €5 extra for a window seat with sight on the Alps? No-brainer.

No-fly zone

But, climate catastrophe. I resolved, to never fly again. My honeymoon was to be the grand finale of all that. It’s a terrible thing to do, flying. To partake in the wholesale destruction of nature, the plunder that is turning the Earth into an impoverished, greatly diminished legacy we leave to our children and grandchildren. A dangerous legacy, with heat supercharging the oceans and atmosphere, extremes of drought decimating harvest yields, extremes of precipitation causing floods and destruction.

You can fly to Barcelona cheaper than it takes, to get the train to the airport of Amsterdam. But it’s not real. The price may seem low, but the real cost is incalculable. Private gains, public losses: the actual costs of environmental degradation are outsourced to distant lands and future generations. An iron grip of colonialism that stretches not just though space, but also though time. And, even more perniciously: spreading like a moral corruption though our souls. To be complicit in the heinous crime of ecocide, and all its terrible consequences, in exchange for a few days of fun in a sunny place. It’s a Faustian bargain of the worst kind. Nobody in their right mind should partake in such cruel, nihilist hedonism.

Slow travel

I embraced slow travel, taking the train to Italy. Choosing not the fastest tunnel route, but instead the scenic Bernina railway that takes the high passes.

Figure 7: Bernina Express

Getting those reservations in place is an expensive struggle, more difficult even than avoiding the upsell buttons of a Ryanair check in.

But there I was, gliding though a snow-covered vista. At the highest station, the train stopped for 20 minutes and I could breathe the mountain air, taking in the mountain landscape from a picturesque little train station. Then, tsak tsak tsak, the power line above the train blew itself up with a bang and smoke. Turning what should have been an early evening arrival at my destination, into a struggle to arrive before public transport cut out, trying to avoid getting stranded at some unsavory, unsafe big city station for the night. You better have a roaming 4G connection and plenty of smartphone chops using foreign train schedule apps, when handling such challenges.

I have warm memories of a sleeper train trip I made in 1992. A time before flying was even conceivable for me: that was something for rich people, and I was dirt poor, a student, freshly divorced to boot. Falling asleep in northern France, despite being encapsulated on a small bunk in a shaking, noisy cabin, surrounded by strangers. Dreamy half-sleep memories of the train stopping and getting re-shuffled mid-way. Then, a glorious peak experience that remains exquisitely vivid even after half a lifetime: waking around six am, stepping into the train corridor, early morning sunlight caressing cypresses, the poetic landscape of the Provence streaming by. I felt transported to a different world, a different climate. A magic new dawn. I had awoken to a dreamy new reality, a different life.

That same carriage still hobbles around Europe, three decades later. The sudden surge in interest in train travel, driven by the recent outbreak of flight shame, has taken train operators by surprise. New train stock is only slowly coming online. Until then, we have to make do with the old 1970s built stock of sleeper trains. On the way back from Italy I took one. Sleeping across the Alps, was the plan. Less romantic than taking the high passes. But saves a hotel night. I got across the Alps alright, but the “sleeping” part of the plan did not work out that well. The bed was too short, and definitely too hard. Add the noise and getting jostled around all night. Not very restful. I’ve done long-distance sleeper train journeys in India, twice, where I slept better.

Figure 8: Indian long-distance sleeper train

Those Indian trains are really something, by the way: they drive on for days, the distance between departure and arrival stations spanning most of the subcontinent, thousands of kilometers. The last one I took there arrived with a two-hour delay, in the dead of night, after I had banged my head on the street in a clumsy fall. My backpack amplified my fall, slamming my head into the pavement, causing a laceration and potentially a concussion. Not an auspicious start for an 800+ km train trip, but it was fine. I slept well and in the morning enjoyed the views of Kerala jungle passing by our windows, while we were served with tea and breakfast.

I sought out long-distance ferries. Drove across Germany to the port of Hamburg. A 24-hour boat ride across the Baltic to Latvia. Having a private cabin is more expensive than a plane seat, but not outrageously much so. A full day at sea, sunshine, calm waters. Reading, listening to podcasts, writing. Sleeping. Lots of time for reflection. An agreeable experience. All the food had seen the inside of a freezer, though.

Figure 9: Baltic ferry

Another trip, I took a ferry from Ibiza to Barcelona. That was shorter and somehow more boring. Then the connecting train across Spain got cancelled halfway. We found ourselves stranded on a weed grown platform of a station that had no entry or exit: it was only accessible by train. Another train took us further. A bus at the end. A kind lady translated the spotty Spanish announcements for me, or I would have been unable to make the right moves at the right moments.

My plan was, to travel back home by high-speed train via Paris. If you do a stopover in Paris, better book at least two nights, so you have a full day in Paris to enjoy the city. Not a punishment, to spend time in Paris. But then the bed bug craze broke out, and I’m thinking: what am I doing? Spending a fortune on lodging and trains, for a trip that takes multiple days, in order to get home with a bed bug infection? I capitulated. I cancelled the trains and Airbnb, booked a direct flight home. Easy.

Gimme a break

Still, I held on to the intention of not flying anymore. What broke the camel’s back was the following winter. Which seemed to last half a lifetime. An endless dreariness of wet, dark, cold deadness that left me drained. Like having my soul sucked out by a Dementor from the Potterverse. I felt like a husk of myself. A zombie. A dim shadow of who I long to be. Coming out of that, something snapped. It’s shameful to confess.

Elections here in The Netherlands played a role in that too. Here I am, trying to do the right thing, denying myself significant opportunities to enjoy life and nurture myself with travel and sunshine. Meanwhile, the people around me vote for far-right assholes. They vote for unbridled nature destruction. For cars and highways and planes and pig farms and police brutality. For anti-woke culture war theater politics, instead of for real solutions.

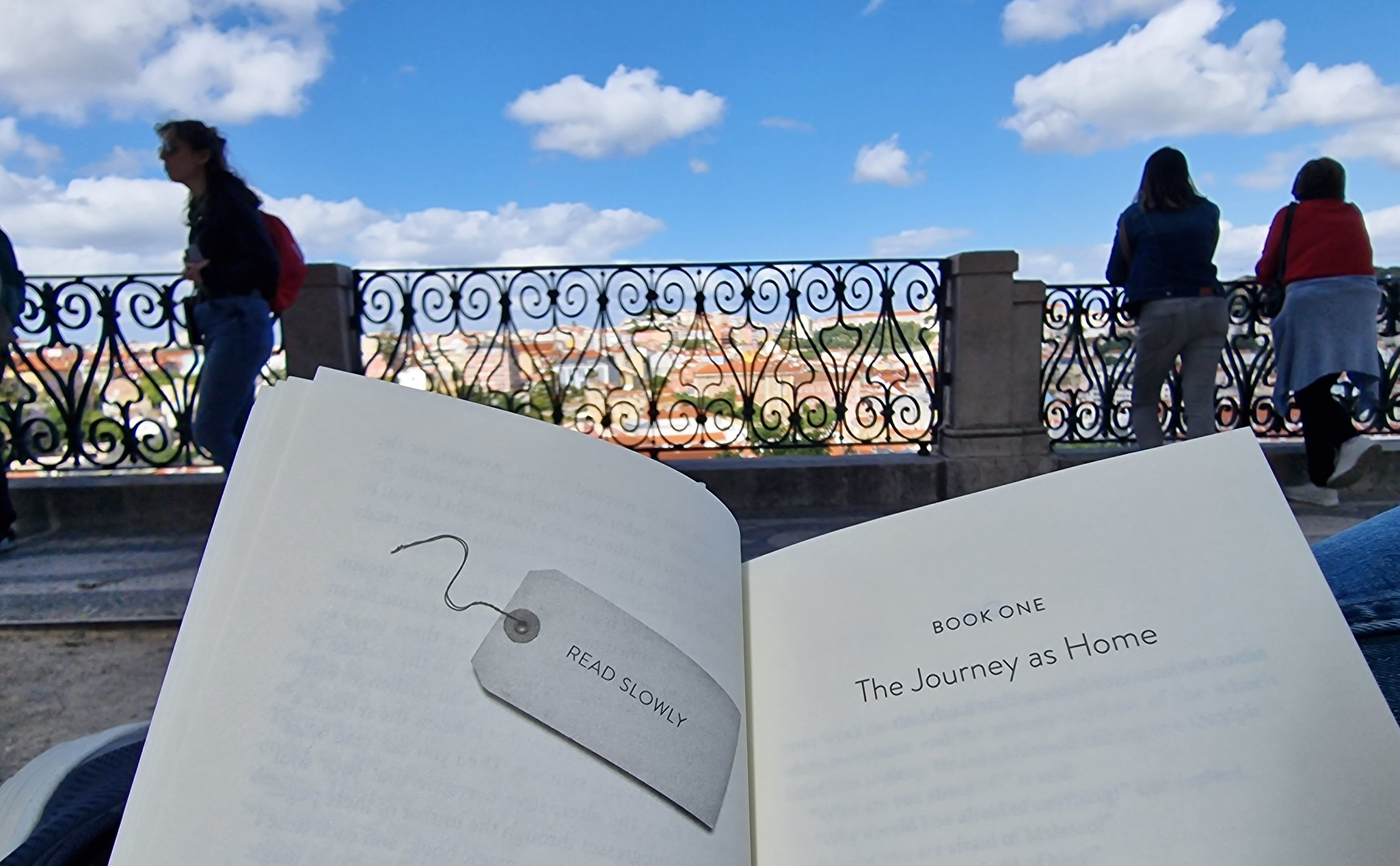

So I decided: next winter I’ll be in Asia. I can work anywhere my laptop has internet; I’ve worked a winter from India before. With my no-fly block capitulated, I went to a conference in Lisbon to get an early taste of summer. It was nice and nurturing, both personally and professionally.

Figure 10: Reading on a sunny Lisbon mirador

The struggle continues

I’m human. I rationalize my choices. Bottom line is: I’m not going to avert the planetary catastrophe by myself. Whatever I do, it hurts the planet. It’s not just the CO² emissions — in my opinion the debate is much too narrowly focused on climate change only. Habitat destruction does not get nearly the attention it should.

Anything I do in this civilization, just being alive, is destructive. All the food you eat, no matter how eco-friendly, has fossil fuel inputs. I have a watch, a phone, a laptop: each of those contains rare metals, which likely involve Congo dirty mines and child slavery. I drive a bike, which is pretty eco-friendly; except there’s a hole in the ground somewhere they blasted the steel out of, another hole somewhere they dug the coal out of to smelt the steel, and a big cloud of planet-heating CO² resulting from the whole process. There’s no escape. Just breathing emits CO² forchrissake.

Using your phone taps into a power grid with a mix of nuclear and coal; it taps into an information metaverse filled with Russian agitprop, incel Nazi idiots and AI spambots. Capitalism is a death machine. The twentieth century was a horror: the twenty-first will be worse. There’s no way, you can be alive and go about your day, without being complicit in the most heinous crimes.

That’s how we all live now. Morally compromised. It’s part of how the system retains its choke-hold. There is no escape. I’ve met someone who invested their life energy into living a different potentiality: who went off-grid, founded an eco-community, lived down-to-earth. Then witnessed the community go sour with infighting, and literally saw their home, their life’s work go up in flames. Ended up alone in an uninsulated flat, watching the single-glass window panes bleed fossil fuel heat into the cold Scottish night. Trying to escape the hegemony of dominator culture, the cards are stacked against you.

Choose love, choose life

How do we carry that burden, of being entangled in this death culture? Of living a life in which each choice reverbs across complex networks though space and time, causing unseen and barely imaginable suffering to others? We cannot just retract in merciless nihilistic hedonism — well lots of people do, but for me that will not do.

At the other extreme, going full hair shirt monk mode in withdrawal from the world doesn’t fit me either. That way of minimizing negative impact externally, implies a level of self-negation that, to me personally, seems like it just internalizes negative impacts. Taking that route to its logical conclusion points to dying as being the most surefire way to eliminate one’s detrimental impacts on the world. That can’t be the point of being alive? But then, what is?

How do I justify flying to Asia, or Finland, or even using grid power to type these words on my rare-earths filled laptop? We, each of us, would have to do massive good in the world, to offset all the damage we’re causing. But then, articulating that, it sounds awfully medieval catholic. Dangerous also, an invitation to cultivate a Jesus complex. So what then, is to be a moral compass that avoids the extremes of either nihilistic hedonism, or life-denying gruff asceticism?

Reflecting on that question, it occurs to me that both nihilism and ascetics share an aspect of hardness. Of indifference. Of shutting out, and shutting down. In my interpretation, at least. So that then points to softness, connection, and openness as potential values to live by. And of course love, and life joy, and wonder.

I need to book my trip to Jyväskylä soon. Either the heavy but more ethical trip by rail and boat; or the fast and evil option of a plane ticket. I’m still postponing that choice.

I don’t have the answers. But I’m searching.

This is my dark edge. What is yours? How do you cope?

Except for the 1972 image taken by my dad, all photographs in this story are my own work – © Guido Stevens