Limits to Growth: To Save the Planet, We Need New Ways of Thinking

The mess we’re in was not only foreseeable; it was foreseen. In 1972 a landmark paper was published: The Limits to Growth (Meadows et al. 1972), hereafter simply called Limits. It’s been called “the most influential science paper of the last 50 years”.

Fifty years after its publication, Limits to Growth is still the best place to start investigating humanity’s prospects for future survival.

Think globally

A key innovation of Limits is, that it introduced a computer model of the whole world. That’s an audacious scope. But obviously, if you want to ponder the future of our civilization at a planetary level, there’s no getting around the challenge that you need to think at the level of the problem you’re solving. That is, planetary.

Interestingly, Limits spends some time on justifying that outlook. It notes that most people are concerned with merely their direct associates (self, family) in the immediate future, say the next few days or weeks. Some people look further ahead in time, and think in decades. Some people have a wider circle of empathy, and think in terms of their nation, or all of humanity, or even all of life on Earth. Only very few people consider the long-term future of the planet as a whole. Well, that has changed a bit in the past 50 years perhaps, and maybe the publication of Limits played a role in that change.

A stunningly simple model

What is perhaps the most surprising in the Limits world model, called World3, is that it boils down to tracking only five key variables through time. Five indicators, to think about the long-term future of the whole planet? That seems ridiculous. To be fair, those five indicators are connected in various ways through various mechanisms. But still. The key variables tracked are:

- population,

- agricultural production,

- nonrenewable resource depletion,

- industrial output, and

- pollution.

That’s it.

Those five indicators are not umbrella variables: it’s not that they are calculating e.g. resource depletion by adding up coal mining, uranium, chromium, whathaveyou; no; it’s as if there is just a single “stuff” that everything is made of, and the supply of that “stuff” is finite.

Same for pollution: you don’t count CO² and Ozone and DDT separately, there’s just the single “pollution” that is increasing everywhere and making life miserable. Same for the other variables.

Five variables, an incredibly abstract and simple way to model something as friggingly complex as the whole world from 1900 to 2100.

A different way of thinking: nonlinear system dynamics

As human beings, we walk around with stone age brains in a highly complex society. Those stone age brains take a lot of shortcuts. One of those, as noted above, is to consider only short-term futures for a select few of “nearby” loved ones. We’ve evolved to optimize survival of our tribe for the next few weeks. Which makes it literally counter-intuitive, and very difficult, to think about e.g. the 24,100 years it takes for Plutonium-239 to merely halve its radiation.

Another of our stone-age brain shortcuts is, that we naturally think in terms of linear effects. Catch two rabbits instead of one, and you’ll have twice the meat. Your family will have food for two days instead of one. Now, if you don’t eat those rabbits but allow them to breed, after one year you’ll have 60 rabbits. Trick question: how many rabbits will you have after two years? 120? No. You’ll have thousands. That’s because not only does the original couple of rabbits reproduce again; all their offspring reproduces too. Population growth is exponential. Unlike linear effects, which add up, exponential effects multiply.

Feedback loops

Limits included such exponential effects in their world model through feedback loops. An example of a positive feedback loop is population growth: the more people you have, the higher the number of births: the larger the population is, the faster it grows. Exponentially. Until it is slowed down by the negative feedback loop of deaths. The larger a population is, the more people die. The crux is, that people do not generally die the day they were born. They live, say 85 years. Which means that there’s a 85 year delay between births and deaths. Because of that delay, the population keeps growing exponentially. Unless some other effect kicks in to change the curve.

If you run out of arable land, people will start dying of hunger. More positively, richer people in general desire less babies and will use contraceptives to make that happen. In terms of the Limits model, that represents a negative feedback loop between industrial output and population growth. The Limits model contains many such relationships between the key variables of population, agriculture, industry, pollution and resource depletion. Some of those relationships are reinforcing, or positive feedback loops. Others are balancing, dampening, negative feedback loops.

Counter-intuitive causation

Somewhere in that complex network of connections, magic happens. The system as a whole exhibits behaviours, where a change in input settings doesn’t quite straightforwardly translate into the change in results you might have expected. Not only are many of the dynamics of the system exponential, which is already counter-intuitive in itself; they also interact in ways that aren’t immediately intuitively obvious.

The end of civilization as we know it

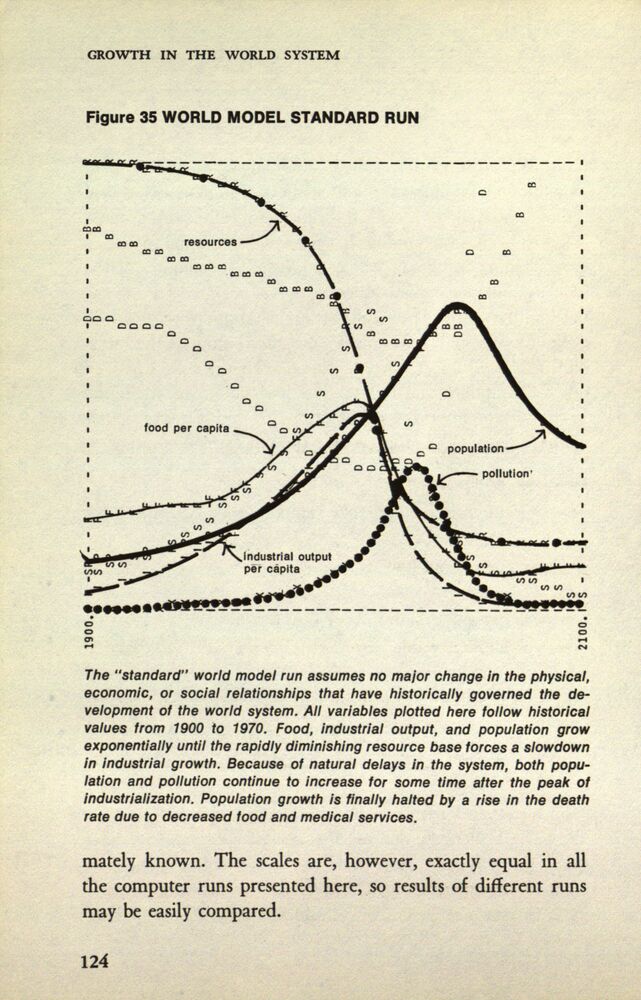

The most famous result of the Limits paper is the Business As Usual graph, reproduced below. It shows the end of civilization as we know it. You see those peaks in the graph? That corresponds to things going south somewhere in the 2030s.

Figure 1: Business As Usual apocalypse (Meadows et al. 1972)

Resource depletion causes a decline in food production and industrial output. Shortly thereafter pollution peaks, and declines with the shutting down of industry. Population keeps growing for longer, and then peaks and declines too.

Which is a very technocratic way of saying: you, your partner, your parents and your children all get very hungry, and very poor, while pollution and despair keep rising. Then you watch your loved ones die of hunger, before you die yourself.

This drives home the key message of the Limits paper: there cannot be unlimited growth of physical resource usage, on a finite planet. Which is rather obvious, you’d think. Turns out, a lot of people (sidenote: One of those even got himself a Nobel prize, as we'll discuss in the next episode in this series. ) .

Scenario variants

In the standard model run of which the graph is shown above, civilization reaches a crisis because nonrenewable resource depletion precipitates a crisis in food and industry, which then in turn cause mass dying. What if we remove the resource problem, by doubling available resources? In that case, industrial output can grow much higher and causes an explosive growth of pollution, which causes pollution deaths and reduces agricultural production. The end result is the same: mass dying.

OK, so let’s have “unlimited” resources by assuming that nuclear energy makes both mining and recycling very efficient. On top of that, governments worldwide intervene and institute effective pollution controls. Not super realistic, but let’s just see what would happen then. Well, we avert the resource crisis and we avert the pollution crisis. Instead, food production becomes the bottleneck. Industry claims arable land, and what land remains erodes because of overcultivation. Again, the end results are poverty and hunger.

And so on and so on. The authors of Limits keep tweaking the model. In the end, the only variants that avoid civilizational collapse, are worlds that combine strong government interventions and significant value changes in people’s minds, away from materialism. Oh, and the kicker? The switchover to a different society has to be made before the year 2000, or it will be too late to avoid collapse.

The whole is greater than the sum of its parts

Those apocalyptic results are shocking. And even now, 50 years later, whole tribes are unable, or unwilling, to accept that we cannot have infinite growth on a finite planet.

But the spectacular nature of those outcomes tends to obscure a more subtle point. The point is not, to calculate in which year civilization will end. The authors of Limits intentionally made the time axis on their graphs fuzzy. The real point of Limits is, that it teaches a different way of thinking. It shows that, to adequately think about long-term whole-planet problems, we have to leave our stone age linear minds behind. Instead, we have to learn to think in terms of exponential effects that interrelate in complex ways. To think in terms of dynamic systems.

A lasting legacy

Which is obvious, in a way. But it’s obvious only once you get it. The lasting legacy of Limits is not just, that it put the possibility of civilizational collapse on the agenda. It also showed that thinking about collapse requires a different mindset, and different tooling. In short, it requires a paradigm shift. 50 years later, a short look at the news will serve as a reminder, how far we still have to go.